🇬🇧 A critical analysis of Milan Fashion Week – Cool Haunted by nss magazine

A lackluster week that left us asking: “What did we truly like?”

The phrase that opened the Prada show notes this season was “What are we capable of creating starting from what we already know?” It could serve as a general commentary on all the shows we saw during this Milan Fashion Week FW26. Surely, we will have to wait for womenswear to see the real fireworks, but over the course of this long weekend, it became quite clear that for many brands, menswear remains a rather limited playing field.

The main issue is that no brand showing in Milan has honestly asked itself how men actually dress in everyday life. With the necessary exceptions, the pendulum has invariably swung between formal suits and the most canonical streetwear imaginable. There have been very few nuances of the Old Money wardrobe and a series of projects that could be classified somewhere between TikTok algorithmic fashion, amateurish efforts, and performative gestures.

As many have already noted, the calendar emptied of big names has left ample space for a series of newcomers, both Italian and international, who have been particularly deserving and, with greater support, could soon turn Milan into a new creative hub.

So then, what did we like about this Milan Fashion Week?

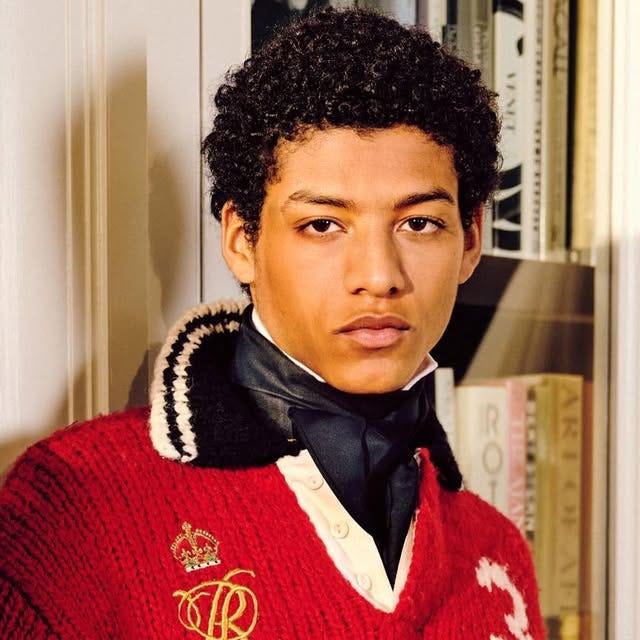

The three brands that emerged best from this Milan Fashion Week do not represent any avant-garde current: on the contrary, they shared a casual confidence in handling tradition and a certain freshness of thought in renewing what is already known, without merely repeating it. The brands in question are Zegna, Ralph Lauren, and Paul Smith. All historic names in menswear, all perceived as classics but, precisely for this reason, all three capable of offering a decisive sense of freshness derived from their honesty: no intellectual twists, no self-indulgence, no amateurish mess passed off as art.

Another common element among all three was the great sense of precision and clarity with which these collections were conceived. At Zegna, even under the earthy and generally dark colors of an old-school wardrobe, the constructions of jackets, outerwear, and suits were absolutely modern, never outdated, in fact, quite the opposite. Ralph Lauren, instead, reclaimed that abundant and lively aesthetic that brands like Aimè Leon Dore had already co-opted for some time, updating it and reaffirming himself as the great lord of American aesthetics at a moment when the American myth the world is attached to is decomposing in real time amid ever-faster online news cycles.

Finally, Paul Smith, a hugely successful designer but positioned outside the dynamics of traditional fashion, without a precise distinctive sign, delivered a simply spot-on collection. The proportions were right and fresh with an inclination toward youthfulness, the styling sober but effective, the style clear and sharp yet carefree, free of heaviness or forced elements. It was pure agility and exactness, far more than what was offered elsewhere.

Another type of fashion seen only in Milan is the flashy, pop, and party-oriented one of Dsquared2 and Dolce&Gabbana. Two brands, each led by an iconic duo, that share a drive toward emphatic, highly vital fashion that doesn’t mince words. Even when, for example, in the Dolce&Gabbana show, it populates itself with gray suits and evening wear. Both brands rely on a sense of machismo that refers to a human archetype, perhaps a bit outdated in its display of presumed superiority and confidence.

Aside from these characteristics (international commentators also had other criticisms regarding the casting), the fashion these two brands continue to propose, and the format with which they present it, are pleasantly free of that sense of haughtiness and snobbery that reigns in other celebrated houses. Could we call it “himbo fashion”? It’s fashion that wants excellence but doesn’t fear frivolity, that is energetic and popular, and in which the runway often becomes a parade.

Moving toward more refined territories, one cannot fail to notice the debuts of relatively new names in the Milanese schedule. Not all the brands in question are absolute newcomers; only Victor Hart and Domenico Orefice are, while the other two, Setchu and Qasimi, already have several seasons behind them. But all four brands managed to bring new things to the runway.

At Qasimi, what won was the measure of colors and fidelity to the recurring theme of capes and drapes that transfigured the classic sartorial uniform. Satoshi Kuwata of Setchu truly complicated things with a collection very (perhaps too?) dense with details that, even just in photos, can seem confusing but are constructed with profound intelligence.

Instead, both Victor Hart and Domenico Orefice worked well thanks to a strong sense of self-awareness. Both designers know what they are and what they want to do. This translates on one hand into the sculpted volumes in denim by Victor Hart, and on the other into the snappy and fresh wardrobe of Domenico Orefice, whose proposal, more mature season after season, has a very clear but immediate and understandable direction.

The best that Milan has to offer in terms of inventiveness, but above all timeliness, are the Italian designers featured in the presentations at Fondazione Sozzani. Of course, it would certainly help for the future if these emerging and independent talents were not literally confined to the far-off Fondazione Sozzani, and could instead be hosted in more suitable locations, such as Palazzo dei Giureconsulti, which in the past has been lent to far less noble functions, including a Shein pop-up.

From the fluid fabric stratifications of Maragno, who this season had in mind a nomadic imagery made of piles of fur and soft lines; to the acidic, Scandinavian pragmatism of Rold Skov, which seems like the Italian response to Our Legacy and Berner Khul. More ethereal, Pecoranera and PLĀS Collective presented interesting experiments with knitwear: the former following a theatrical and dramatic direction, with long knit dresses, details almost sculpted in the fabric, collars and corsages entirely in knit; the latter opting for a lighter, decorative, and feminine mood.

The most interesting of all, however, remains the sardonic and almost decadent Meriisi, which evokes rocker atmospheres with an all-Italian sense of vintage and an almost diabolical taste for idiosyncratic clothing. For this collection, the brand mixed the classic leather biker jacket with a Toy Story T-shirt, applied an exposed zip to wool trousers that highlighted the groin, or equipped knitwear with crystals, embroidery, and a sense of irony that practically begs to be expressed on a runway.

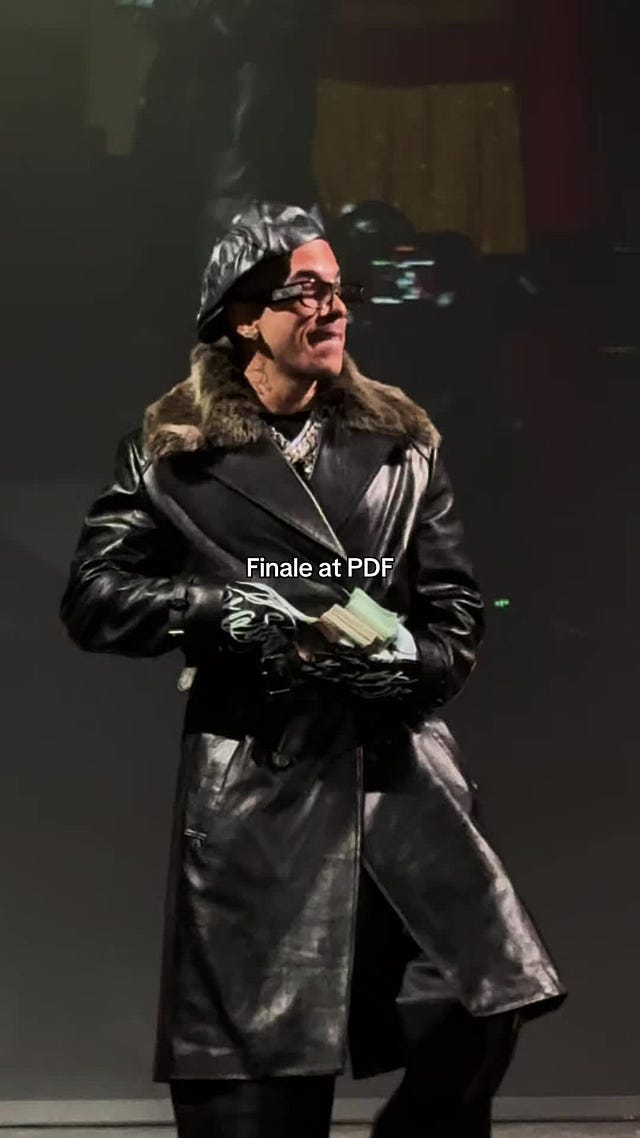

If the week opened with the sublimation and reworking of sartorial tradition at Zegna, the closing by PDF seemed like a sign of the times. The brand founded by Domenico Formichetti is the spokesperson for a new generation of Italians. More multicultural, raised on the myth of American hip-hop, and for whom personal style is not about the extreme elaboration of craftsmanship but the most blatant and unsubtle declaration of a new type of aspirationality.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

In Formichetti’s show, the clothes gained meaning and aesthetic weight as stage objects in a five-act theatrical narrative that turned the narrative conventions of classic gangsta rap into a role-playing game for a bourgeois youth that still cultivates the myth of the street, weapons, gang feuds, easily earned and easily squandered money.

And finally, it’s indicative that at the PDF show there was a community not of haughty “very important clients” arriving from the four corners of the planet, but of true brand enthusiasts, mixed with press and buyers in a crowd that, as a more seasoned journalist recalled at the entrance, wasn’t too far from those of the shows in the ‘80s. So, is this the closing of a circle or the opening of a new cycle? We ask ourselves this, also wondering whether Milan will know how to adapt to changing times.