🇬🇧 Hosted By: Renaissance Renaissance

The founder and creative director Cynthia Merhej talks about colonialism, creativity during wartime, and what it means building a fashion brand in the Middle East

Leggi l’articolo in Italiano qui

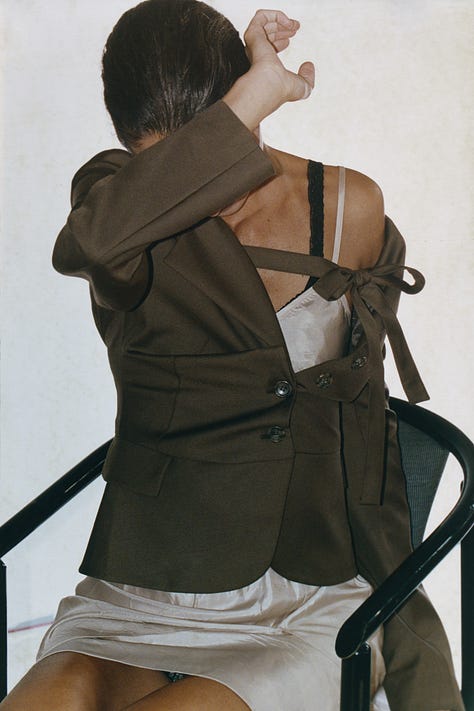

Not many brands can say their first viral moment of the year landed on January 1st, but for Renaissance Renaissance, 2026 started with a bang. Founded by Cynthia Merhej in 2016, the label has grown at a time when separating fashion from politics, place, and lived experience has become increasingly difficult.

Characteristics made visible, almost as if it were by fate, when Rama Duwaji chose to wear Renaissance Renaissance FW23 for the inauguration of her husband, Zohran Mamdani, as the newest mayor of New York City. Put simply, a woman of Syrian descent wore a Lebanese brand for the inauguration of the first Muslim socialist mayor of America’s most influential city.

Over the years, Renaissance Renaissance has followed a trajectory that resists easy categorization. While the brand and its atelier are based in Beirut, Cynthia Merhej has lived and worked between Paris and Lebanon, allowing the label to move fluidly between local production and international fashion circuits. Production has remained rooted in her home country, with select phases also developed in Italy, building a language centered on rebirth, continuity, and evolution. As it approaches its tenth anniversary, change emerges as the defining theme of this pivotal year: change within the brand, but more importantly, within an industry Merhej deems as «unsustainable, especially for independent designers».

Renaissance Renaissance is now approaching its 10-year mark. Looking back, how would you describe the evolution of the brand, and how does the idea behind its name reflect that journey?

It’s been a roller coaster. The brand has stopped and started several times - every time things began to gain momentum, something disruptive would happen. In the beginning, it looked nothing like what it is today. The pieces were very basic, and I was basically only selling to friends through pop-ups. The brand as people know it now, with more intentional and developed creative collections, really began to take shape later, around 2018 or 2019.

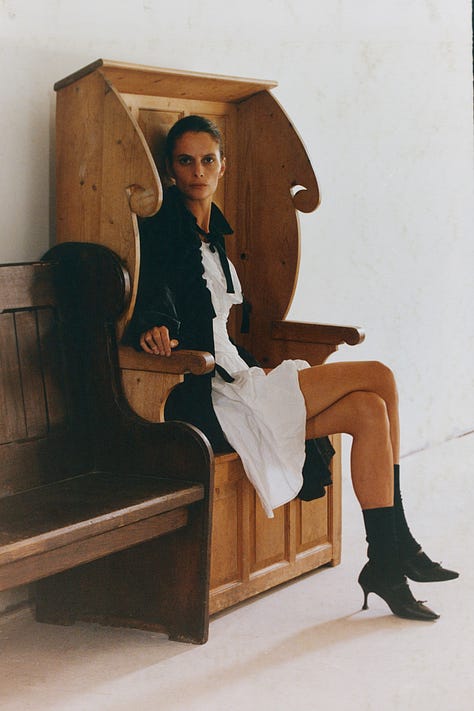

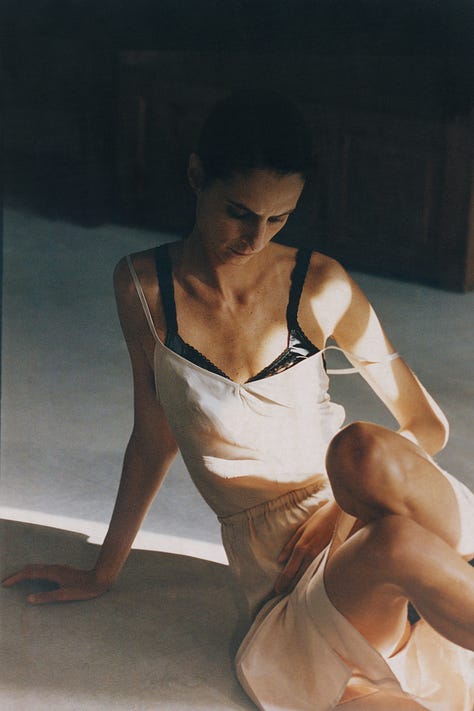

That evolution is also exactly what the name Renaissance Renaissance stands for. My ethos comes down to the idea of rebirth and transformation, not only in people but also in garments. I really believe we’re not the same person throughout our lives, and I like the idea that clothes can reflect that, moving with you through different phases. Sometimes you buy something and don’t even wear it until years later, until it suddenly feels right and becomes part of your life in a new way. That sense of circularity, of things returning and evolving over time, is central to my work.

You’re a CSM alum, but you didn’t study fashion design. What led you to enter fashion, and how has that non-traditional background shaped the way you work today?

My mother is a couturier, and so was my great-grandmother, although I’ve never met her. Fashion felt like a natural language for storytelling ever since I was a kid, but I didn’t want to follow a path that felt predetermined or expected. At the beginning of the brand’s life, I sometimes regretted not studying fashion design because school gives you time and space to figure out your voice. Instead, I had to do that in real time while also building a business and trying to survive. But looking back, I’m actually grateful because I saw friends study fashion and end up hating it, and I think not having that experience helped me keep a more naive, playful relationship with it.

As a Palestinian-Lebanese person, the past few years must have been extremely difficult. Did you find comfort in your art, or was it something you struggled with? Are any of your collections directly inspired by your cultural background?

Living through bombings and drones overhead is not an environment that makes creativity easy, but you learn to adapt because stopping only benefits the people who want you silenced. There was something deeply absurd about trying to sit and think about clothes while everything else was unfolding.

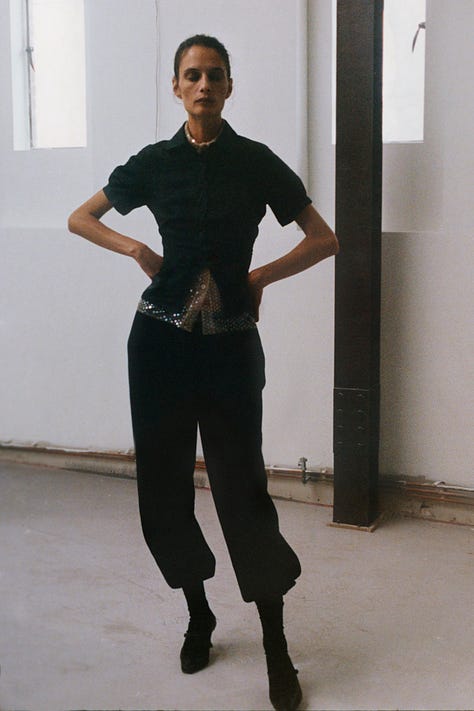

The first year was especially hard, and I think that darkness came through in the FW24 collection. But you can clearly see how I started to feel slightly more hopeful with the SS25, and I wanted to address those themes in a way that felt personal, bringing some lightness back into my own process. A big part of it is also reframing the narrative. Palestinians and people from the region are often reduced to victims, but we’re also artists and creatives who continue to make things despite everything.

You’ve been selected both by Fashion Trust Arabia and the LVMH Prize. How did these two experiences differ, and what do they reveal about the relationship between Eurocentric and Middle Eastern fashion ecosystems?

Colonialism taught us for a long time that what we have isn’t valuable, but more and more people are beginning to unlearn that. When Fashion Trust Arabia first launched, there was really nothing comparable in the region, and many of the judges involved came from European institutions. As a result, the experience could sometimes feel similar to established Western platforms. But right now, there are so many different cultural incubators growing in their own direction, gradually becoming less dependent on European validation.

The LVMH Prize was also an incredible experience, being recognized there is a milestone in any designer’s career, but Middle Eastern fashion is still often framed as something “new” by that audience. At the same time, representation is slowly expanding. When I was first nominated in 2021, I was the only Arab woman designer but by 2025, there were three of us from the region.

Renaissance Renaissance is 100% Made in Lebanon, yet the brand is based in Paris. How does this juxtaposition shape the identity and storytelling of the brand?

Actually, we now fully operate from Lebanon. I initially relocated to Paris because between 2020 and 2024, it became nearly impossible to function here. Lebanon went through a financial collapse, hyperinflation, protests, Covid-19, and then the port explosion. There was no electricity, no banking system, no stability. At one point, we were literally making clothes with my grandmother’s old pedal sewing machine. It wasn’t sustainable, so I had to leave in order to keep the brand alive. Now things are slowly stabilizing, and being back here means being closer to the reality of production and to the people I work with. The brand’s supply chain is very vertical: everything is nearby, within a short distance.

Realistically speaking, moving your brand to Paris would have been the easiest choice. Did you choose to stay in Lebanon as an act of rebellion towards the fashion system?

No, and honestly, Paris was never the easier option. I have no money, I’m not French, and setting up a business there is incredibly expensive and prohibitive. Being in Lebanon was more accessible because people here wanted to support me and be part of what I was building. There’s also a different working culture, people hustle, things move fast, and there’s a real sense of collaboration.

That spirit made me feel more engaged, and it made the work feel meaningful. At first, staying felt like the easier way to begin, but now it’s a conscious decision. It’s not rebellion for rebellion’s sake, it’s a commitment rooted in what I want this brand to represent and where I want the value to remain.

You recently released a short film about the brand on Instagram, and change was a major theme of the story. What is something you wish to change within the fashion industry?

The biggest realization for me is that you can’t wait for change; you have to do it yourself. Especially inside a Eurocentric system, chasing validation as a non-white person can become a trap. That’s also why it’s important for me to consistently mention my heritage, I don’t want people to assume Renaissance Renaissance is a French brand just because it circulates in European spaces.

I’ve noticed that simply stating that we are Made in Lebanon already shifts perspective, because so many people still assume something can’t be this good and come from here. Challenging that assumption is part of the change; I’m not waiting for the industry to evolve, I’m trying to embody the change I want through how I work and what I insist on naming.